On August 25, the Minnesota Department of Health declared the measles outbreak within the state to be officially over. With 79 total cases, it had been the largest outbreak since 1990. Most of the victims were children under ten.

On August 25, the Minnesota Department of Health declared the measles outbreak within the state to be officially over. With 79 total cases, it had been the largest outbreak since 1990. Most of the victims were children under ten.

The first case was diagnosed on April 11, and the last was identified on July 13. It is standard procedure for a measles outbreak to be declared over if no new cases are identified for 42 days. Measles has an incubation period of three weeks, which means it takes that long for someone newly infected with the disease to start showing symptoms. Health officials therefore wait two incubation periods before announcing the end of an outbreak just to be on the safe side.

During the 1990 outbreak, 460 people developed measles, and three patients died. During this last outbreak, over 8,000 people were exposed to measles, and 22 patients needed to be hospitalized. Seventy of this year’s cases were located in Hennepin County, while four were in Crow Wing County, three were in Ramsey County, and two were in Le Sueur County.

According to the director of the Infectious Disease Epidemiology, Prevention and Control Division at the state’s Health Department, Kristen Ehreshmann, many of the measles cases could have been prevented if people had gotten vaccinated beforehand. Of the 79 people who had gotten measles, 71 had not been vaccinated.

The first patient was one these: a Somali-American child who had probably been infected at the end of March. That gave the disease at least ten days to spread to other unvaccinated people before health officials could intervene.

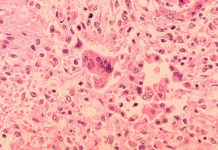

Measles is highly contagious, and the virus can linger in the area for hours after an infected person has left the room. The measles virus is spread through the air when an infected person coughs or sneezes. In addition to the characteristic rash, patients also develop a cough, runny nose and a high fever.

There are two vaccines that can prevent measles. Unfortunately, local anti-vaccine groups have convinced people that the vaccines can cause autism. That myth was the result of a research paper by Dr. Andrew Wakefield which was discredited years ago. The belief that vaccines caused autism persisted, unfortunately, and vaccination rates declined, especially among Somali-Americans. The health department worked with schools, day care centers, Somali community leaders and health care providers to immunize as many unvaccinated children as possible to reduce the number of potential victims.