Nature Communications, a trusted, peer-reviewed scientific journal that’s been publishing studies since 2010, published a groundbreaking piece of research titled “Sequential LASER ART and CRISPR Treatments Eliminate HIV-1 in a Subset of Infected Humanized Mice” that reported that a cure for HIV, or the human immunodeficiency viruses – we most commonly refer to them in singular form, though there are actually two viruses, not one, that are responsible for what turns into AIDS if not treated – had been found for mice.

The researchers, who all hail from the University of Nebraska Medical Center and Temple University – all 32 of them – managed to have their groundbreaking, ultra-innovative research published by Nature Communications two days ago, on Tuesday, July 2, 2019.

To start their studies, the academic researchers gathered a group of highly similar mice. There were 23 mice, referred to as “humanized mice” by the researchers in the study they collectively pumped out however long ago that was ultimately published on Tuesday, July 2, that took part in the groundbreaking study. From there, they were genetically modified to pump out the T cells of humans, which are lymphocytes, which are a class of white blood cells that are responsible for killing unwanted microorganisms such as contagious pathogens.

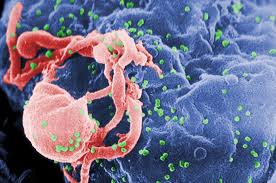

All of the T cells pumped out by the mice that were created by the jam-packed cohort of scientists were highly susceptible to coming down with serious infections of HIV.

The researchers employed a technique called long-acting slow-effective release antiretroviral therapy, a relatively new means of preventing viruses found inside the body from splitting up and multiplying as quickly as they would when left grow in most people’s bodies. Also known as LASER ART, the form of therapeutic treatment can also be used to keep either of the two strains of the human immunodeficiency virus’ populations from growing.

Next, researchers used existing technology related to CRISPR, an acronym that’s short form for clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats, that allowed them to get rid of or add certain genes in the particular human immunodeficiency viruses that were pent up inside each and every one of the 23 mice’s bodies.

The technology utilized in CRISPR-Cas9, the name of the specific form of CRISPR used in this study, was first described in 1987 by Yoshizumi Ishino, an educator and human genetic researcher at Japan’s own Osaka University.